The Road Less Traveled – by Kris Clewell

I’ve driven my 1972 911 over 44k miles in the last 4-5 years. I couldn’t believe it once we’d figured it out. Some friends and I had been sitting over pizza, wondering how much it costs every time you redline the engine. 5 cents? 10? We never really nailed down a figure, but we did find an old odometer photo back from when I rebuilt the motor. I compared it to the current reading. I creaked back in my chair, crossed my arms, and wondered how the miles stacked up so fast. Road trips out east, Road America trips, visits to my parents, groceries, rides with my daughters, and living in the outskirts of the city really added up. I’d martyred myself every summer for almost 5 years to take in the sights and sounds of the world around me from behind the wheel of an early 911. The problem was that most of the miles were trivial: the interstate, errands, and stoplight-to-stoplight driving that was eating my car alive and wasting its potential. As much pride as I took from rolling into the local Target on the way home from a spirited drive, something was missing.

I had planned to fly out to Monterey for Car Week to shoot and write a piece, and I had to get out to Laguna Seca to do it. I decided I’d drive, take my friend Alex Nelson, a documentarian, as co-pilot, camera guy and motivational booster. What could be more in the spirit of car week? My martyrdom eroding, I decided 90 hours in the car was just too much. I shipped the 911 to LA, where Alex and I picked it up at the StanceWorks garage, covered in dust and grime from the trip. I slid in and started navigating the grid of Costa Mesa looking for a car wash.

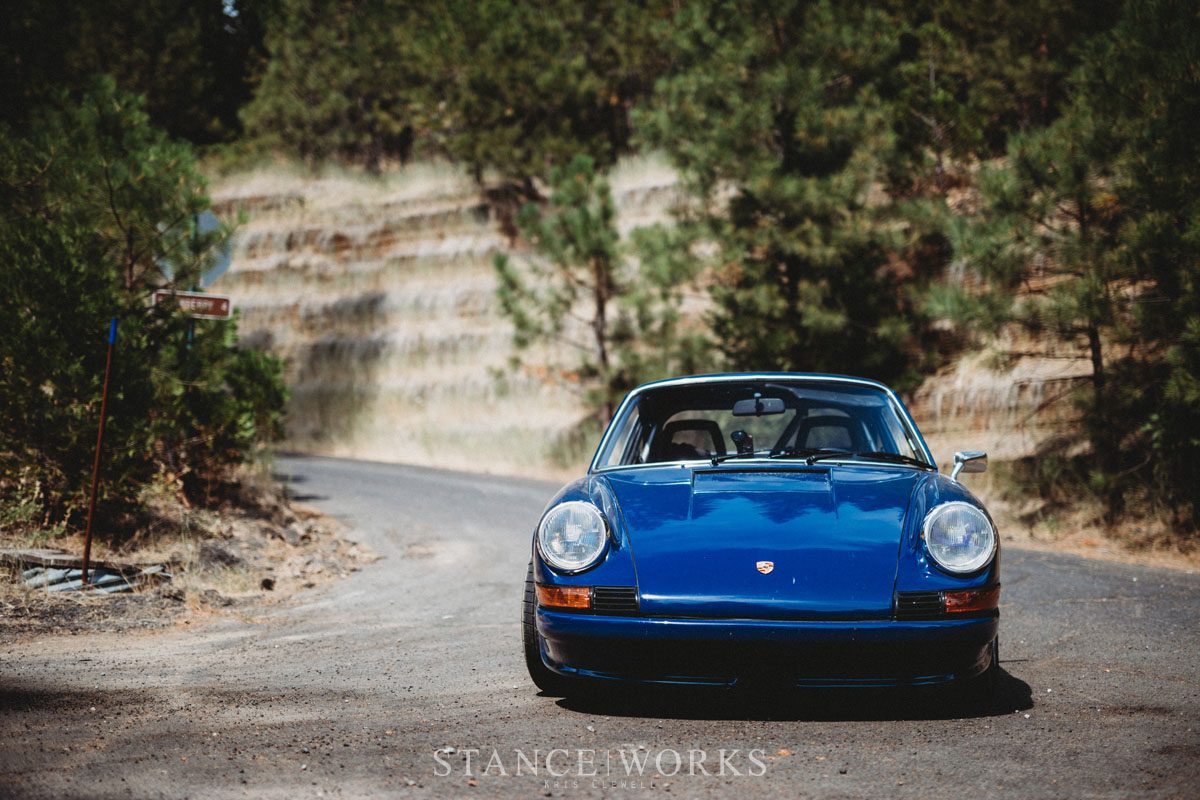

It felt like California, and I felt hip enough, so I pretended I belonged, wearing my 911, sunglasses, and cool shirt I’d bought before I left. There was no rust on cars that would have been dust back in Minnesota. The car spotting came easy. The buildings were low, industrial. I pointed at Porsches peeking out from behind half-closed garage doors. Vintage BMWs were either for sale or waiting in a lot nearby. Every gas station could wash your car while you waited. I peered through mini palm trees at the guys washing the 911. Wincing as I watched it dry in direct sun, I wondered if this trip was a good idea at all. I couldn’t afford to fix the car if something catastrophic happened. I had brought along a few tools, and some parts that typically go bad: an ignition box, a coil, a few other odds and ends. Realistically however, if something bad happened, I’d be stuck. I built the motor myself, and wouldn't have anyone else to blame. The nerves had built up for months before the trip. I became an automotive hypochondriac, worrying that I’d heard it miss, something was vibrating, or that the temp gauge was too high

We rolled away about an hour later, the car clean but emanating a strange odor from the scent they sprayed inside. It was all interesting, but not the California I’d hoped to find. With the haze of the Midwest washed off, we headed west. Cranes started to appear on the horizon as our journey led us to the Port of Los Angeles. I stopped for a photo and security was on me immediately. We escaped south to Long Beach. Anonymous retrosynth was barely audible out of the bluetooth speaker I’d rigged under my dash. Skateboarders were filming, people were wrapped in towels heading to the beach, distant ships crawled along the horizon, waiting to unload their cargo at the port. I parked the car by sand that stretched past a pier far into the distance. This was the California I’d expected. We filmed and shot a bit, and headed back to Los Angeles to crash.

The 5:00 AM wakeup came without complaint as we arose to film with the Stanceworks crew off road at Big Bear Lake. We loaded our gear into the 911, the trunk up front full and the roll cage hugged by camera equipment. Alex at 6’6’’ didn’t fit much better than the luggage. After a weary run out of the city, we watched the sun rise over the San Bernardino National Forest. The roads would have been brilliant had we been alone. We were already running ahead of the Toyota FJ crew (loaded up for off-roading) but still got pinned behind others. As we climbed in elevation, signs reminded me to turn off my non-existent air conditioning to help with overheating. I checked my gauge, and the car was indeed getting hot: 210, 215, 220. At around 5000 feet I downshifted to pass. Nothing. Generally, 240 horses in a 2300-pound car moves me apace. But this was my first time driving in real elevation and the lack of throttle was a reality check. With no o2 sensors, and no computer to help adjust for the elevation, the car ran rich. Bogged down, the 911 turned into a momentum car: less brakes, more knuckle. I did my best to keep the speed up and manage the traffic. As I chased up the mountain Alex exclaimed about how beautiful the vista was. It became the story of the trip. My eyes were on the road, and his were on the scene. The way down was easier. I let the engine do the work. A Ford Focus suffered in front of us, smelling of brakes and stress. We coasted into a gas station in a flat below Big Bear. The corduroy recaros offered better relief than vinyl or leather, but I was still soaked with sweat.

I walked into the station and asked a woman in a violet shirt and matching purple eyeshadow, nail polish, and hair binder where we were. She called me honey, and said we were in Lucerne Valley. I pulled out my phone and looked it up. We were at the outskirts of the Mojave Desert. The Grand Tour had filmed the intro sequence to their series premiere here. Great. All I knew was it was 105 degrees, and I couldn't drive over 60mph because the fan could not compensate at higher RPMs for the increased heat. We coasted as much as we could, sometimes for miles on gradual descents, 80 and even 90mph at idle, flying silently past sunken RV’s and isolated mailboxes with no houses.

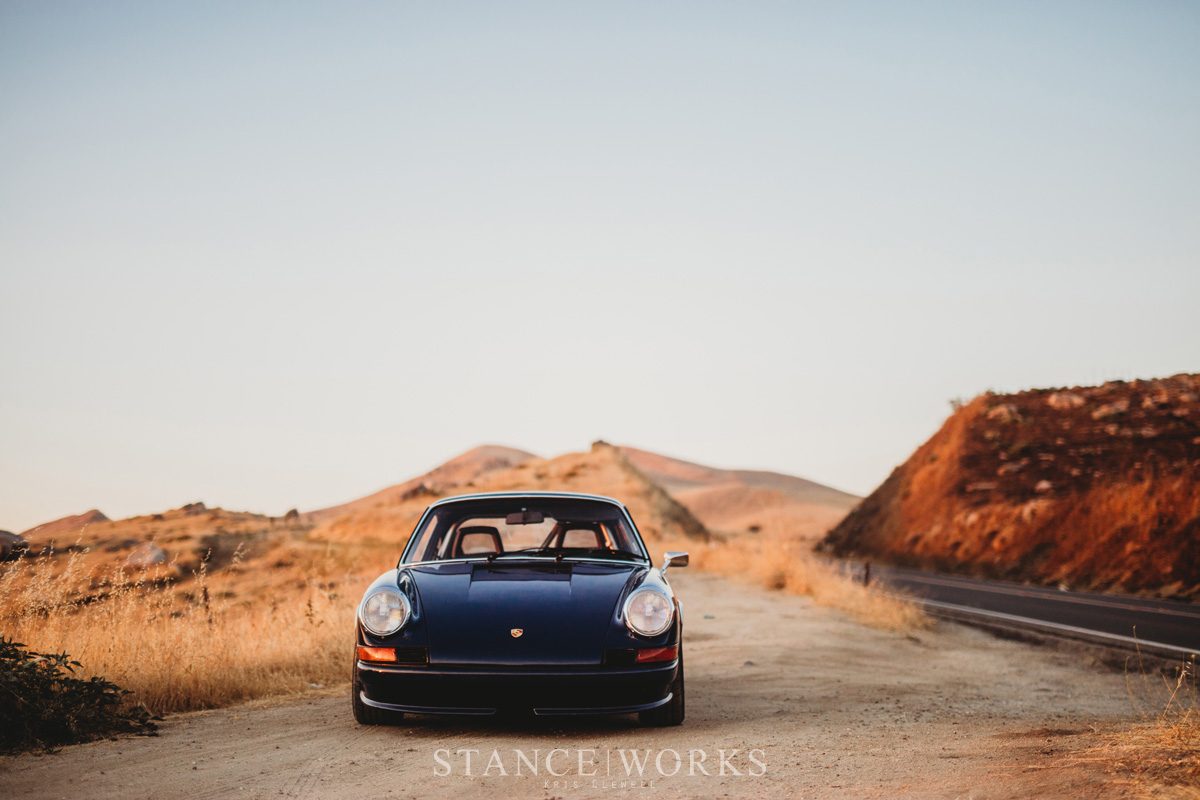

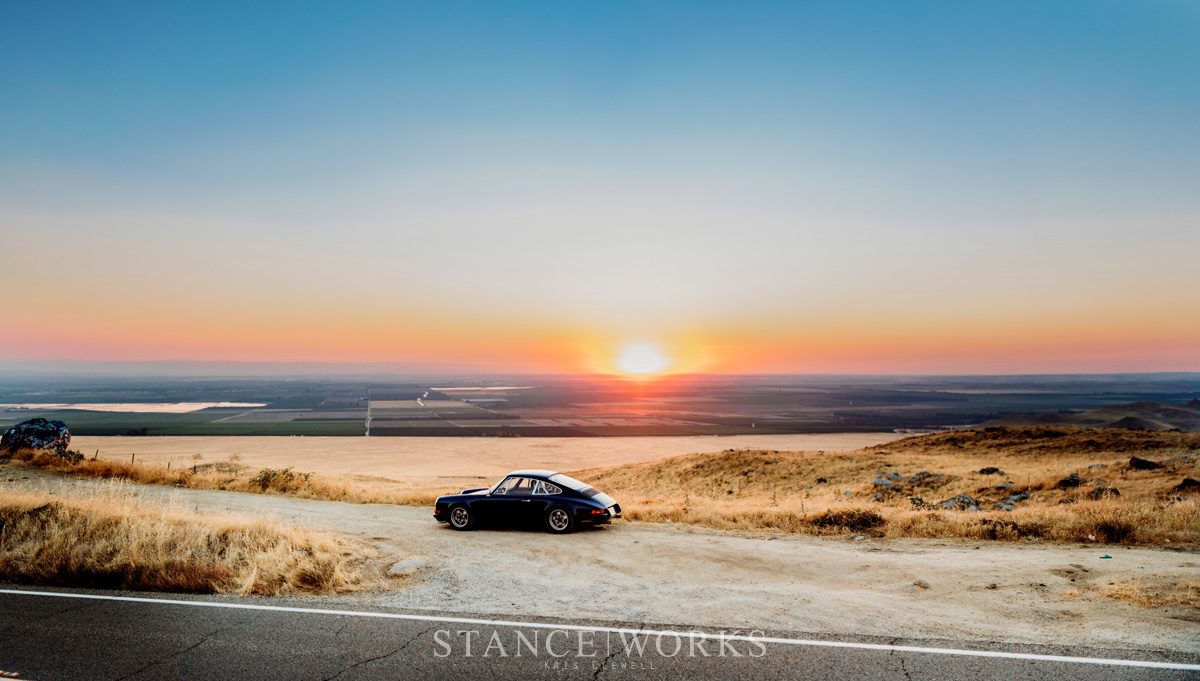

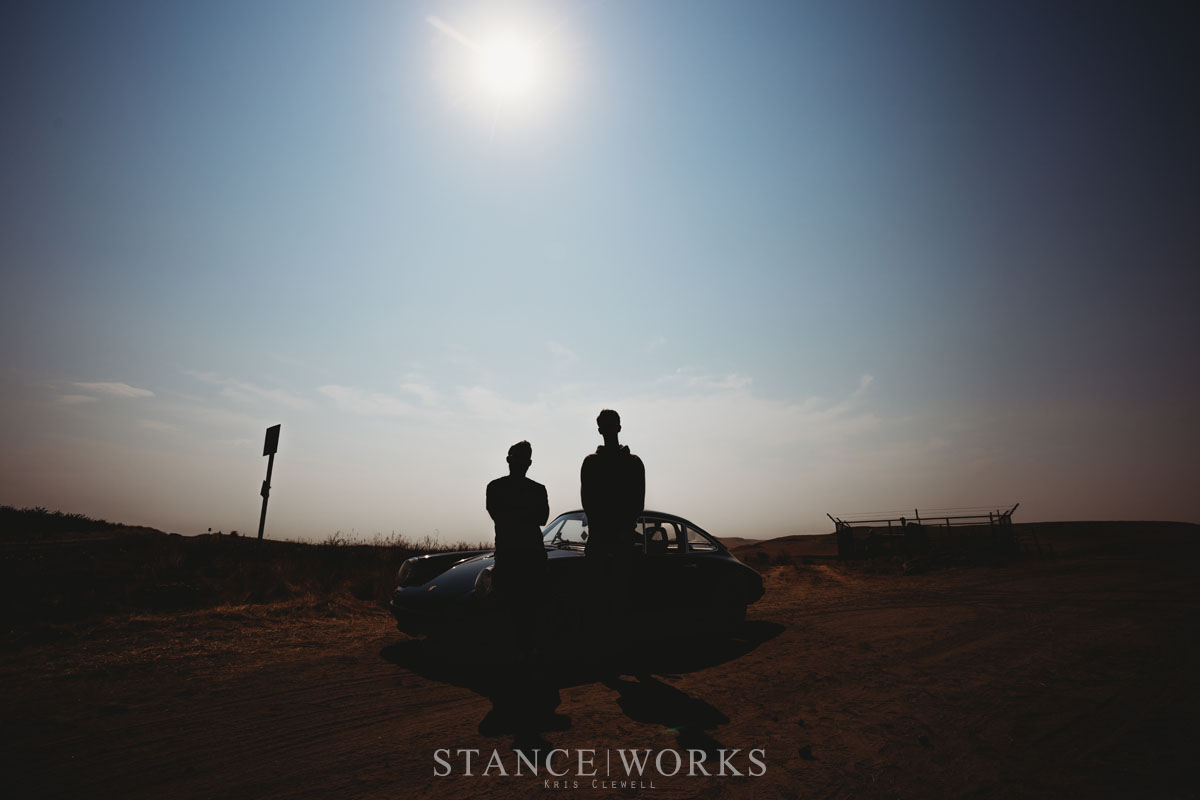

The desert eventually gave way, and we found ourselves on an old section of Route 66. I needed evidence that I’d been there, but the gift shops we hit had no bumper stickers, no decals. It became an obsession. I stopped at truck stops, gift shops, and gas stations. Nothing. Google beeped that there was a faster route, and wondered whether I wanted to take it. We peeled off from the state road and headed due west toward a town named Arvin. We drove above what must be the fertile basket of California, fleeing the elevation down a ridgeline. The road cut through the rock we left behind. To our right, we could see the setting sun. I don’t really remember the rest of the drive from Arvin to Monterey, but I’ll never forget seeing the sun set there. We parked thousands of feet above a grid of farms, the haze in the air painting a soft palette as the sun drifted down. We scrambled to take a few shots, and filmed what ended up being one of the more special moments of our trip. It was there that I finally thought I had arrived.

We pulled up to our rented house in a town near Monterey at around 11pm Sunday. It was early in Car Week, and the town seemed quiet, and inconsequential. I won’t turn this article into a piece on Car Week; the scope is too large, it would be like counting sand with a telescope. The best I can do to sum up car week: it’s a bit like being waterboarded with outrageous cars, and the only break from the deluge is sleep. Even early mornings are filled with people shuffling to and from different events. As the week goes on the pressure increases and acclimation to the uptick is impossible. Cars existing only on posters step off the wall into reality. Imagine the surprise of seeing a Ferrari F40 drive by in your home town. Translated to car week that same situation is akin to being run over by three F40’s, five 959’s, and a 250 GTO. It’s an incredible place to take your car. I was surprised to get waves and smiles in an old 911 that existed in the wake left behind by the best Europe, Asia, and America have ever offered. The week you’re there you have escaped the real world. Driving away felt like turning the page on a fantasy novel you can’t ever read again. The week was instantly stamped as nostalgia and filed away in my mind. Monday morning we left Monterey behind and headed east.

Being mired in the Midwest is a blessing, right? Winter, fall, spring, and summer mark the passage of time. In the winter, the snow and salt-blanketed roads keep cars inside, providing a natural “wrench season.” You’re (trapped) inside your home or garage, looking out. It’s warm, comfortable, and motivating. In Minnesota, we’ve got a few good roads carved out by the Mississippi, but car culture here is lived vicariously by most. Blogs, magazines, Vlogs, and television feed us the latest. Exploring the rest of the country, and what roads it has to offer, doesn’t happen often in the Midwest. It should. Isolation is no excuse. Despite all the mileage I’d piled on the car, it had all been in the Midwest and east coast. I spent time mapping out a route home from California: LA to Monterey, Monterey through the Sonora Pass into the droughted landscape of Nevada. We’d take canyon roads through Utah, into Colorado, and then pound the interstate home.

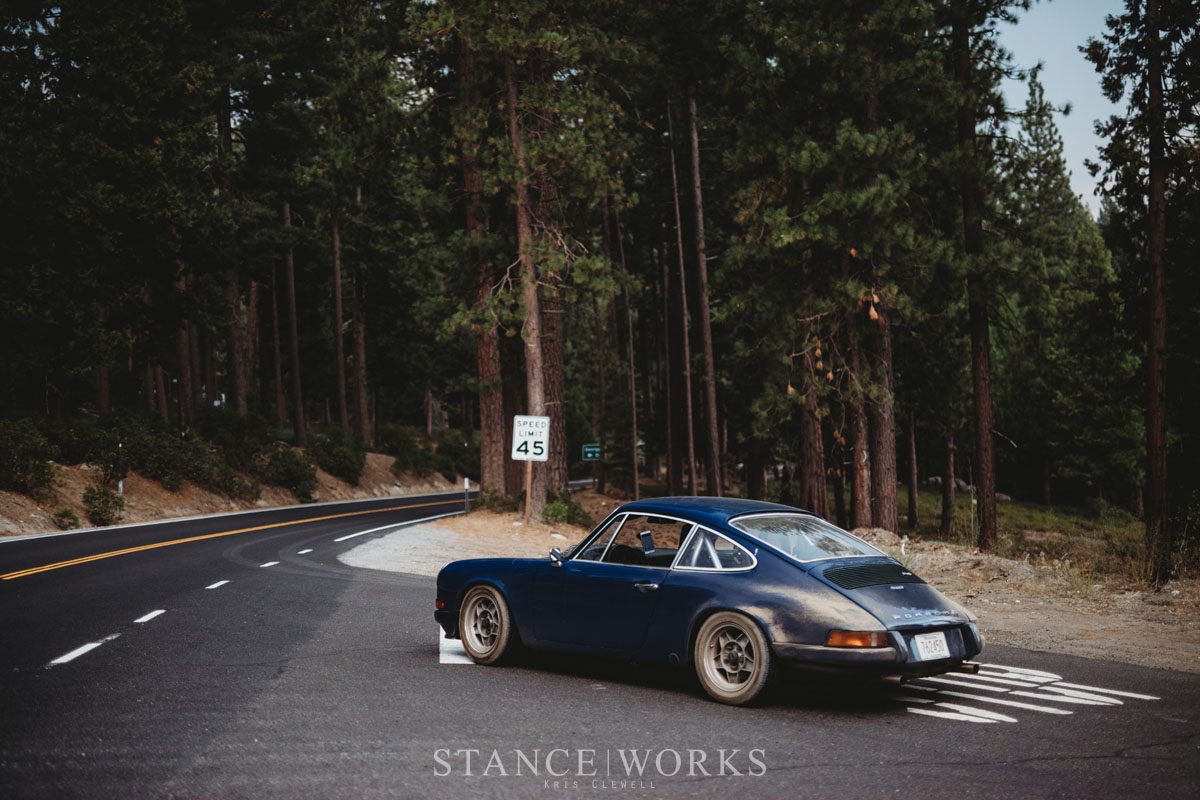

We’d take two-lane roads all the way to Denver. In total, the base route added up to 43 hours of driving time and just over 2800 miles. In the end we would pile on over 3500 miles. We traversed the decreasingly populated landscape from Monterey to the Sierra Nevadas. We knew the eclipse was happening that morning, and once the time got close we grabbed a hard right onto the first obscure road we could find off the state highway. A few miles seemed like enough, and we pulled onto a silty side entrance to a huge ranch. The light changed, but never seemed to get darker than an eerie glow. The rancher drove by on his ATV and lent us a welding helmet through which we saw the sun as a tiny crescent in the black rectangle. Anticlimactic to say the least.

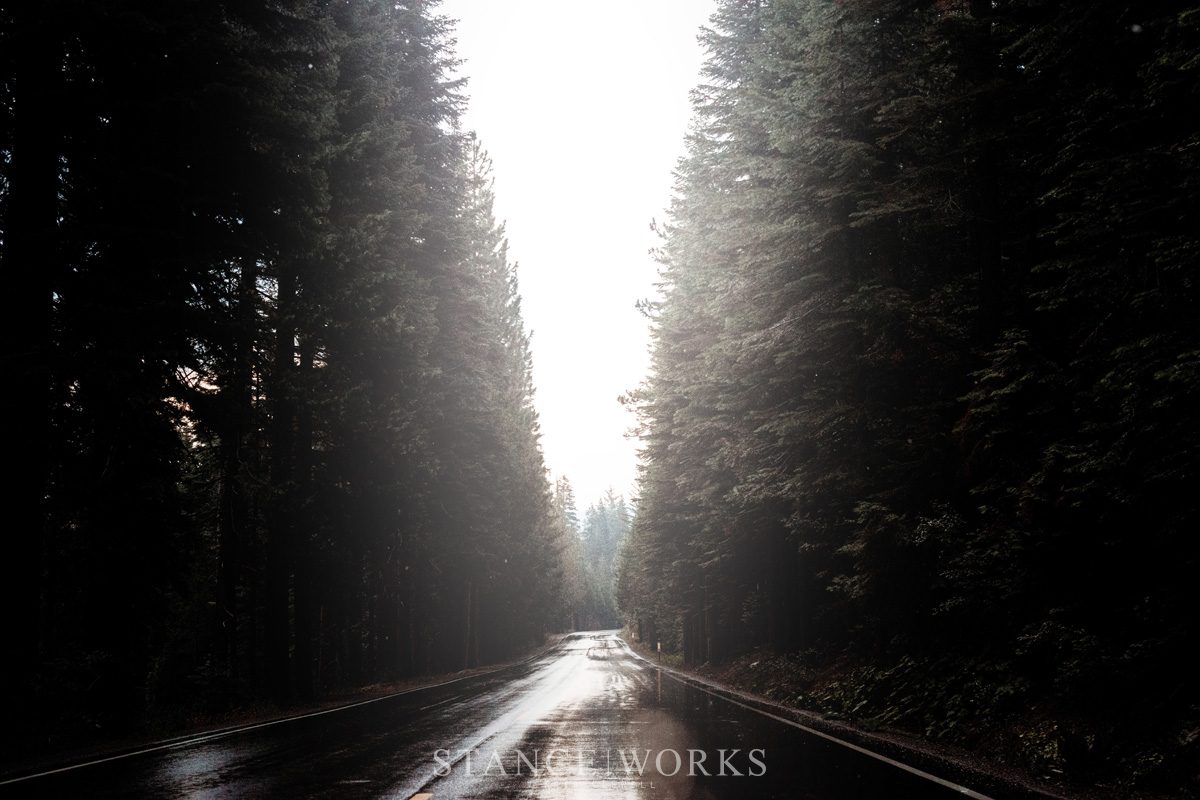

Our first hotel stop was Mammoth Lake CA, but first we had to make it over the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Driving through Yosemite is the obvious choice, but I’d already driven that route. Not to mention that this time of year it was bound to be clogged with tourists. A quick search for an alternative suggested the Sonora Pass via CA route 108. With a constant grade of at least 8% and some sections peaking at 26%, I was confident we’d see less traffic, fewer RVs, and no trucks. Despite our lack of power, we explored some side roads, but several proved difficult to pass in the 911. We spent 45 minutes traversing 4.5 beautiful miles of a logging road. The reward was a dirty tan gradient down the side of the car and a serene look at the Stanislaus Forest. Boulders that dwarfed my car were still under a swath of Jeffrey Pines and White Firs. Everything seemed as if it had always been there. The density of the trees shielded the overlooks we’d gotten used to and removed the usually obvious elevation. It was our first sense of feeling as if we were nowhere.

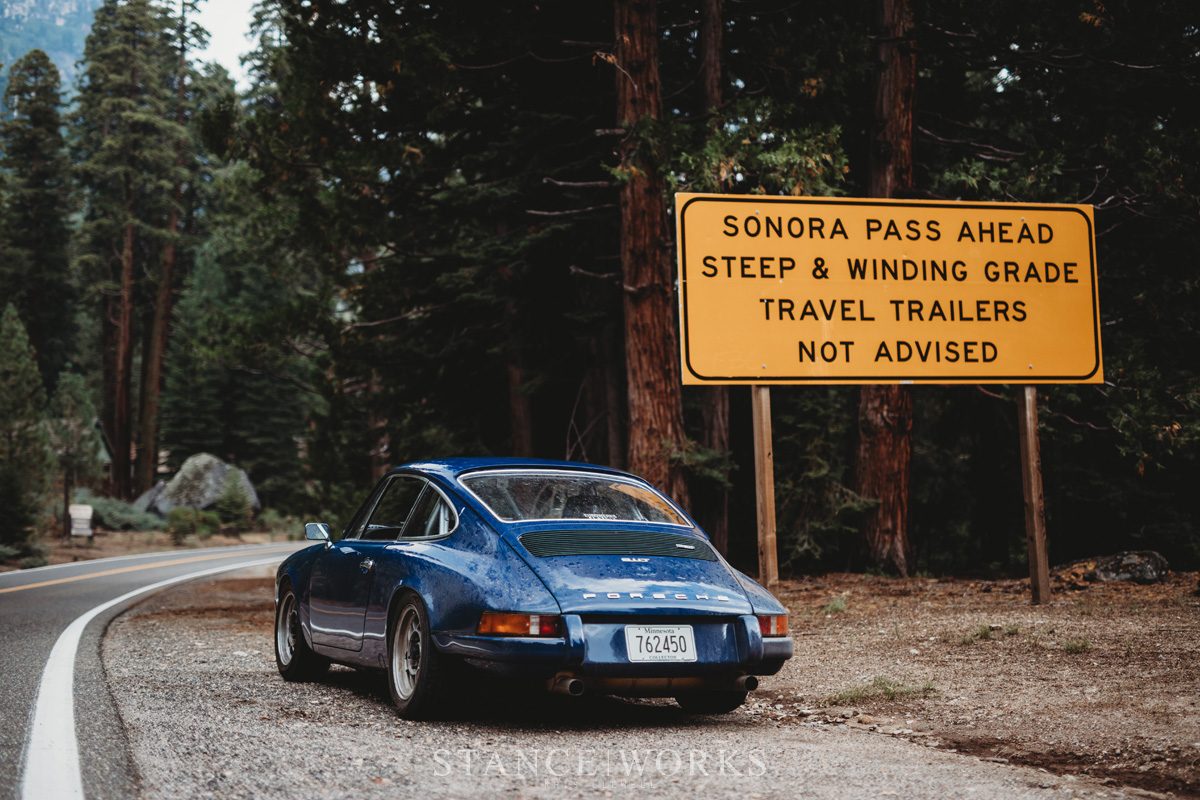

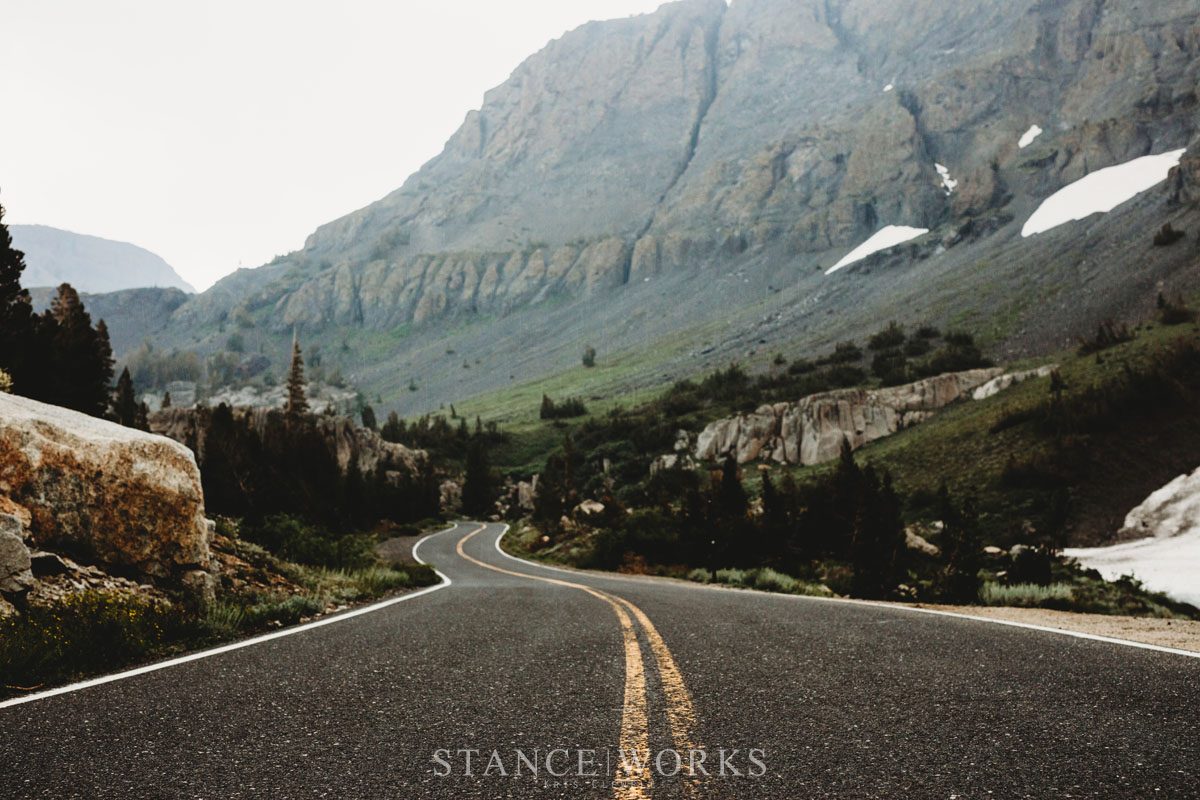

As we left the logging roads, we turned back on 108. Drops of rain spattered the dust that had accumulated on the car. A few more miles and we pulled up to an ominous sign: “SONORA PASS AHEAD STEEP & WINDING GRADE TRAVEL TRAILERS NOT ADVISED.” It was the sign I’d been waiting for since being disappointed by the eclipse earlier. It was still raining, and now thundering. An F150 barreled by us hauling a camping trailer. I saluted him, and played sad music in my head for his approaching demise. We pulled out just as more thunder shook us. I’m used to being under storms, but at 8000 feet we were in it. The thunder sounded like two boulders being slammed together and dropped next to us. A few miles up the F150 sat on a pull off. The sad music played in my mind again, and I hoped he would turn back. The inclines ahead were monumental, blind, and dangerous. The shoulder was small, and the rain slowed me down. Vistas went unnoticed as I focused on the road in front of me. The pass itself came up without drama. It was just there. Startled, we pulled over for a few photos. I hopped out, stood up, and immediately saw stars.

As a Midwesterner, my body was ill acclimated to the elevation. As we started down the other side of the pass I was dizzy and foggy, my mouth dry. We stopped to film and take a break just after the pass. We watched as clouds fell purposefully over the mountain peaks from the storm chasing up behind us again. When we continued, the peaks stepped back, surrounding us as we tried to make up time across flat basins. Our stops to film, and the slow and steady speeds, cost us time: A predicted 7-8 hour journey took 12. We were exhausted. Near our hotel was a beautiful road, but I only recognize it in hindsight. The sun glittered through huge pines. Signs as wide as my lane warned that the turns were hairpins, and to use caution. They were deeply banked, and swept us right up to our hotel door like a nightcap.

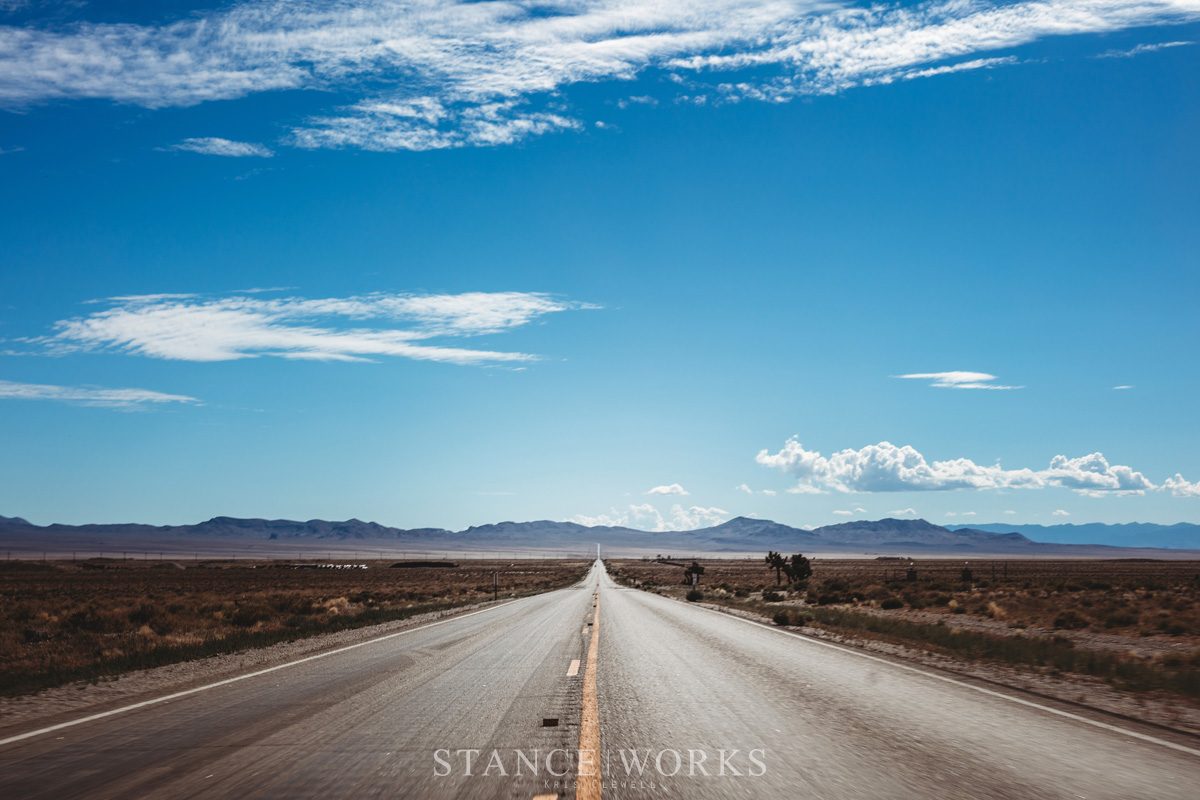

The route across Nevada into Utah was difficult to pin down. The route I had planned took us across Nevada mostly on Route 6 and would take 8 hours. Worried that we would again run behind, I was determined to stay on state routes instead of the interstate. We managed to shave 2 hours off our time, but it cost us a lot more. I thought once we left California and the Sierra Nevada mountains, we’d gain our elevation back, and I’d again be able to pound away on the car and row through the gears. We’d be staying in Escalante, Utah, 550 miles and 9 hours away. There were two things I’d really looked forward to on the trip; one was in Escalante, and the other was the vast lonely expanses of Nevada. We came out of California into Nevada through the Inyo National Forest. But, where we went through, the forest isn’t a forest at all, it’s Inyo National Shrubbery. Sparse in ecology and humanity, it was nothing but small rocks and saltbush varieties with an occasional yucca tree. Roads were straight for miles. Shallow playas formed depressions in the landscape. Time was marked only by the passage of one depression to another. The scale of the western US isn’t measured by mountains, but by the negative space occupied by each individual section of lonely highway. We drove open range to open range, and from desert to desert. The massive shadows of entire clouds lay on the ground in front of us.

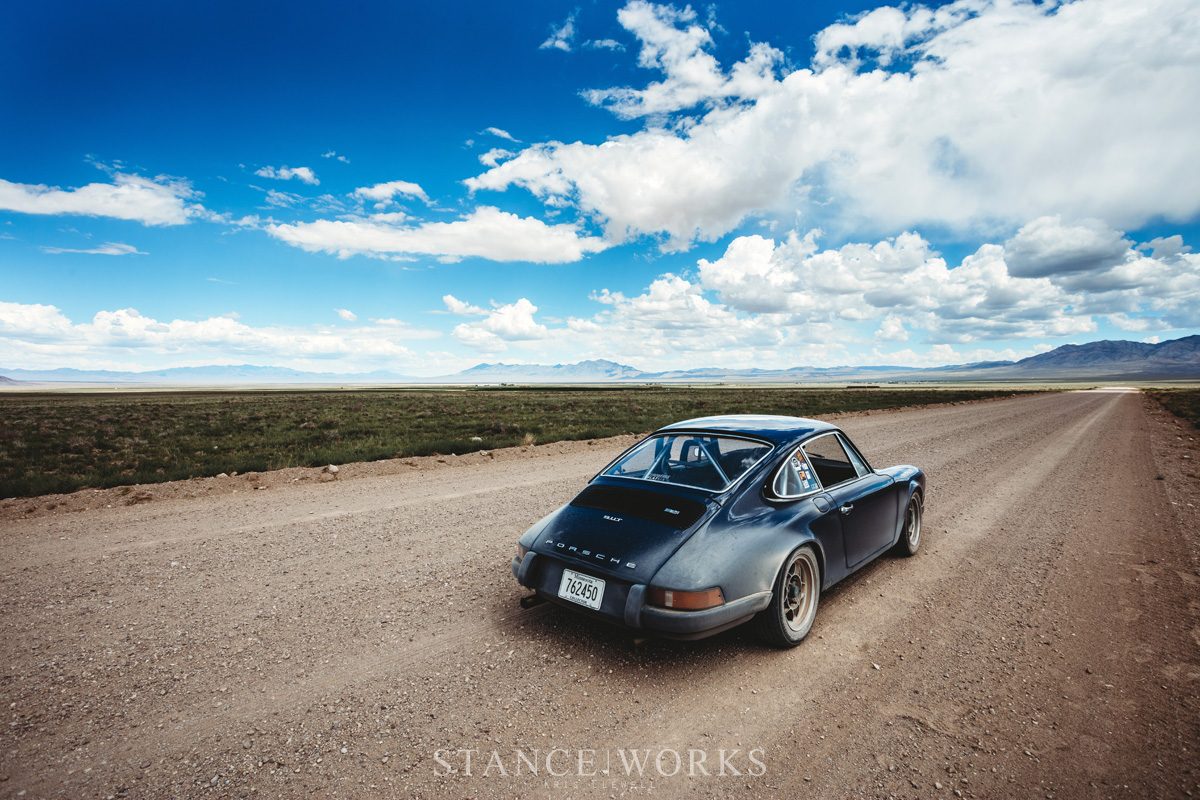

Route 6 gave up to Route 375, colloquially known as the Extraterrestrial Highway. It’s marked with a strange sign just before Rachel, NV. Near Rachel is Area 51. I parked at a small gift shop by a rusty truck carrying a ufo. I picked up a map of the area, some tequila and a rubber alien. On the world's shittiest map was an X that read “Back Gate to Area 51.” A mere 12 miles of gravel roads separated now separated me from frozen aliens and experimental robot humans. I was in.

It was the nicest gravel road I’ve ever been on. I cruised up the road to the gate at 50mph. I knew it was legal to drive up to the gate but my nerves still skipped. We counted 11 cameras/sensors pointing at us as we pulled up. I snapped a quick photo, and headed back down the long road. It felt immaturely dangerous, like stealing baseball cards from the gas station, or not slowing down for the cop pointed the other way in the median. On our way out, an F18 hornet flew eerily quiet in front of us. All the low-flying aircraft signs we’d seen that had not been realized were vindicated. It scrambled away 100 feet off the ground in a full banked turn, in my mind clearly keeping a red alert federal eye on the imminent threat presented by tired and sweaty Minnesotans in a dirty, non-air conditioned 45-year-old Porsche.

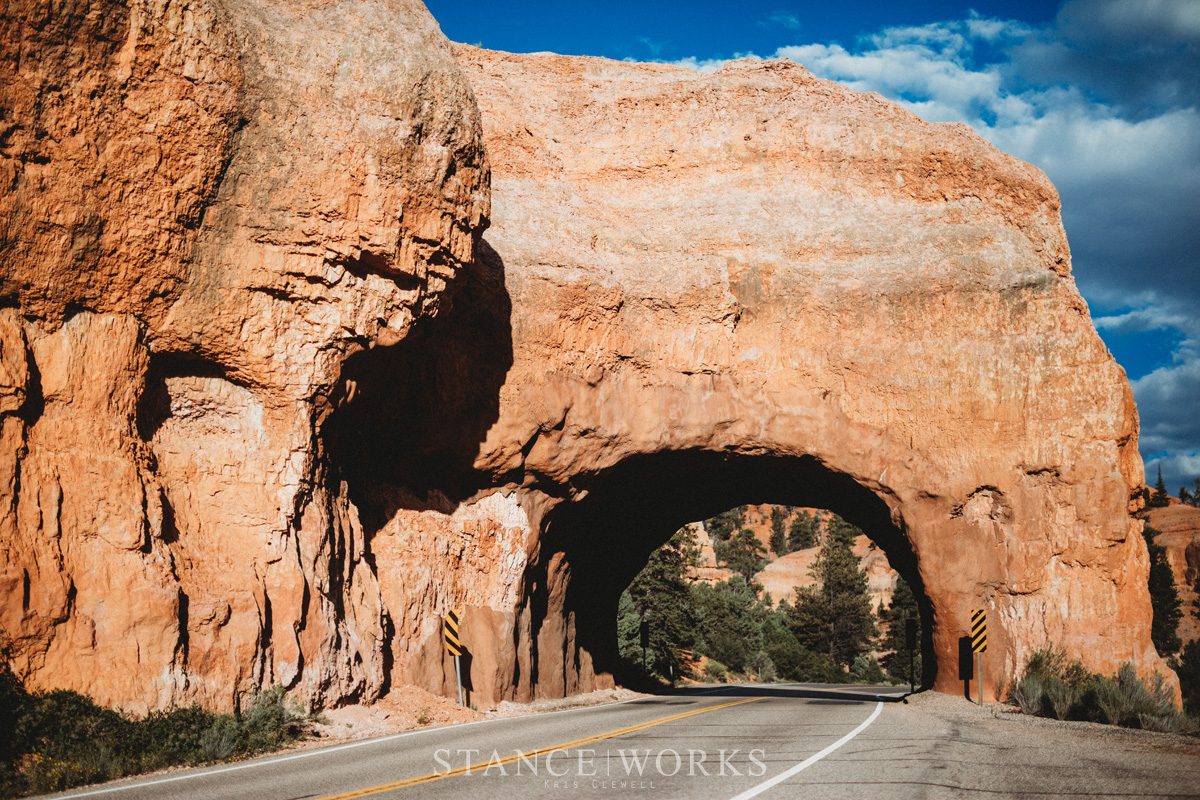

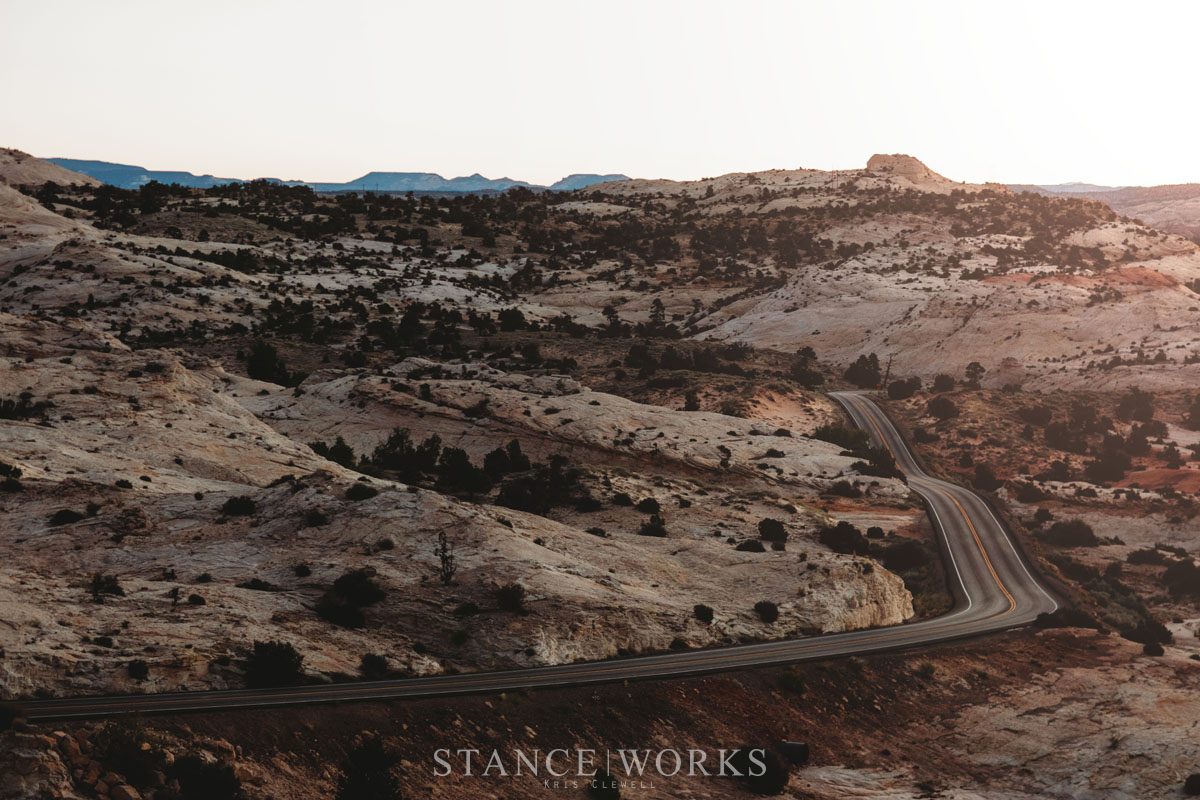

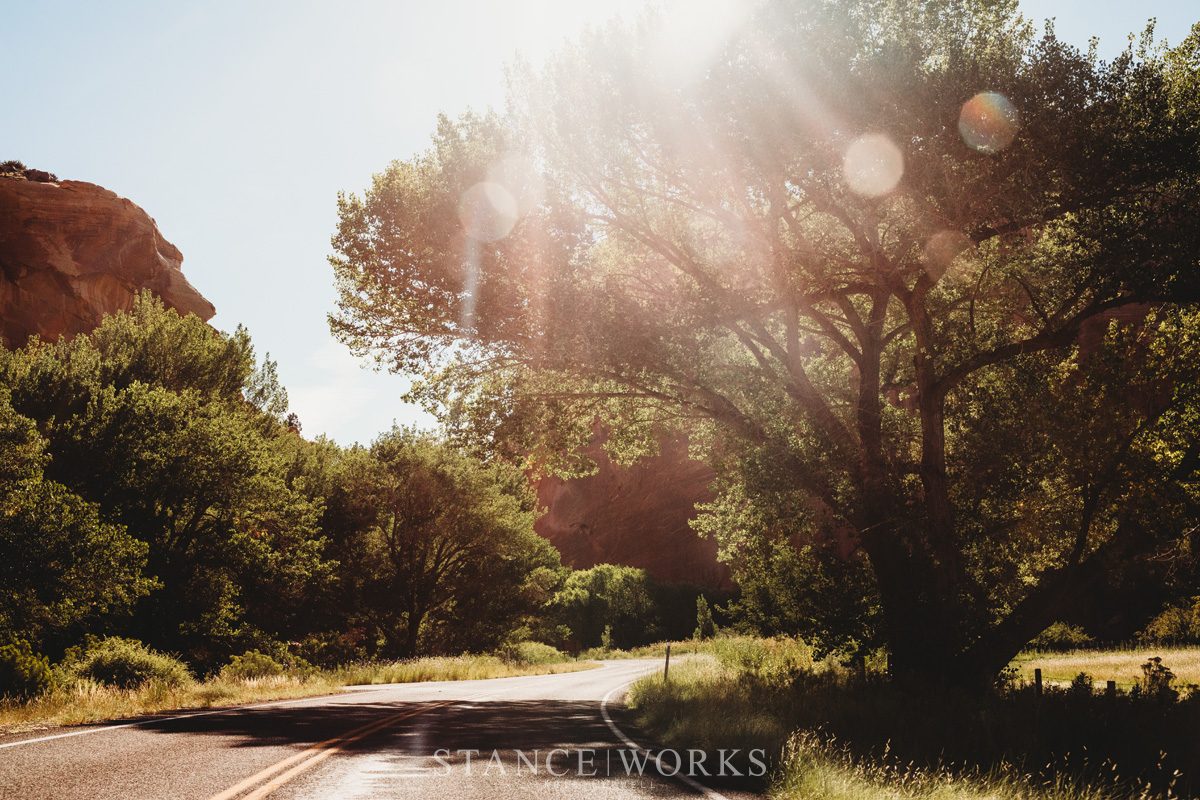

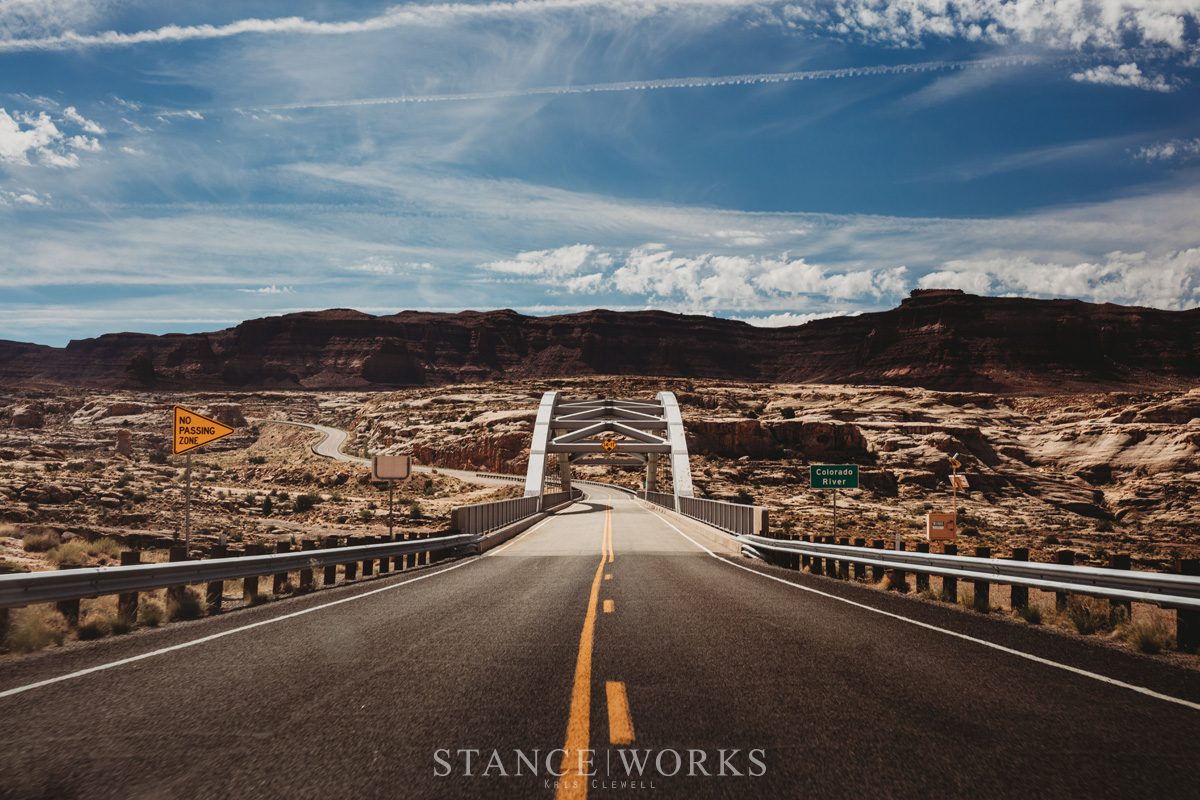

Back on Route 375, the width of the depressions shrunk, and red rocks became apparent on the small mountains on the horizon. The roadside was lined with yellow flowers, seemingly welcoming us out of a wasteland and into the red carpet that would become south western Utah. I’d never been to Utah. The mountains started their slow changeover to the trees of the Dixie National Forest. Volcanic rock lay right up next to the road. Instead of the small rocks you could hold in your hand, they were huge, and stretched off into the distance amongst the trees. I still had less power in the car, but I’d acclimated to it by managing the oil temperatures on the ascents and the brakes on the descents. Determining our elevation was a constant guessing game. It never seemed to drop much below 6000 or even 7000 feet. I realized as I passed people that I must be doing fairly well with the car. I could see cars and trucks struggling to pass others, and even though I was down on power, I didn’t seem to have the same trouble. Sitting in construction somewhere at whatever thousands of feet in Utah, I did notice the fuel pump was whining excessively. I had another, but hoped I didn’t have to use it. We chased after the sun, knowing it would set near our arrival time in Escalante, and we wanted to do a shoot somewhere in the red rocks, and the canyons. We passed a few spots hoping for something better. We finally pulled into one of the many abandoned farms scattered throughout the wastelands. The fence leaned over, its barbed wire pulled off the posts and curled, imitating the prickly shrubs underneath. I watched the sun accelerate down behind a distant cliff, its diameter seemingly disappearing faster once it touched its crest. Magic hour poured across the valley. We continued on to our stop for the night, exhausted again, but feeling an earnest complacency in making it across the desert trouble free.

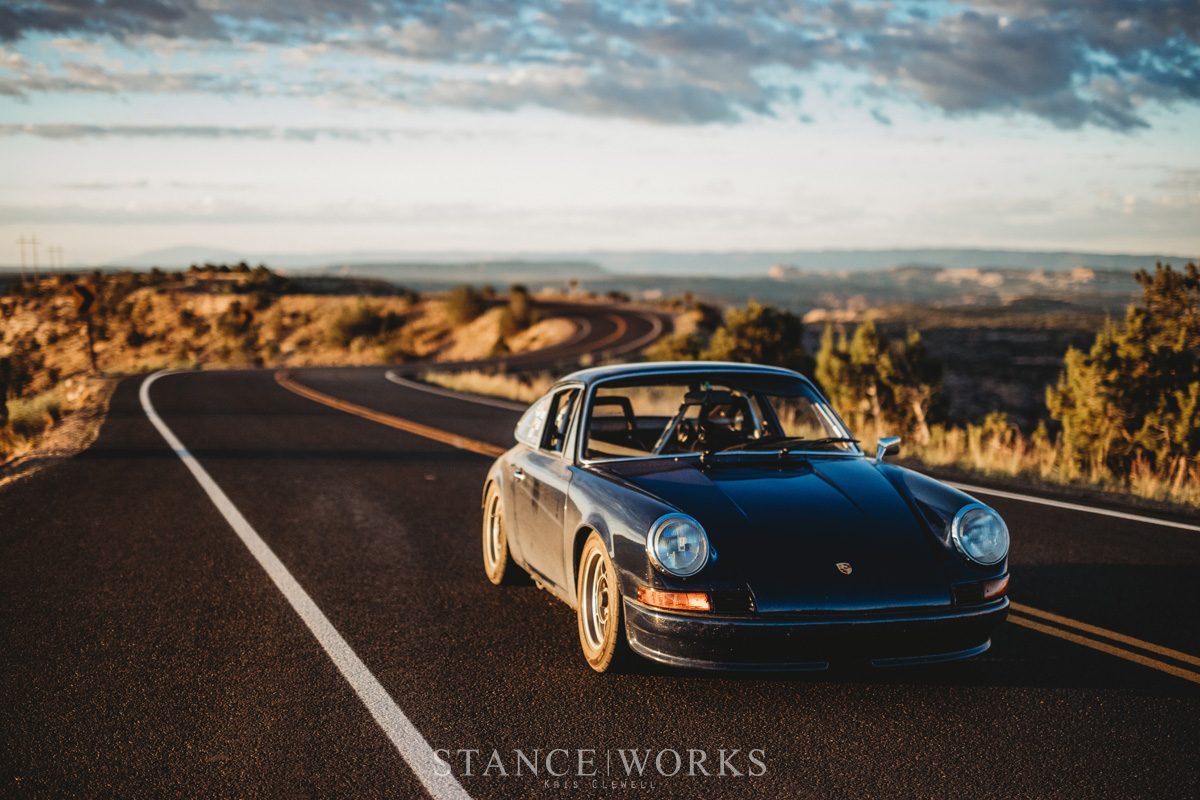

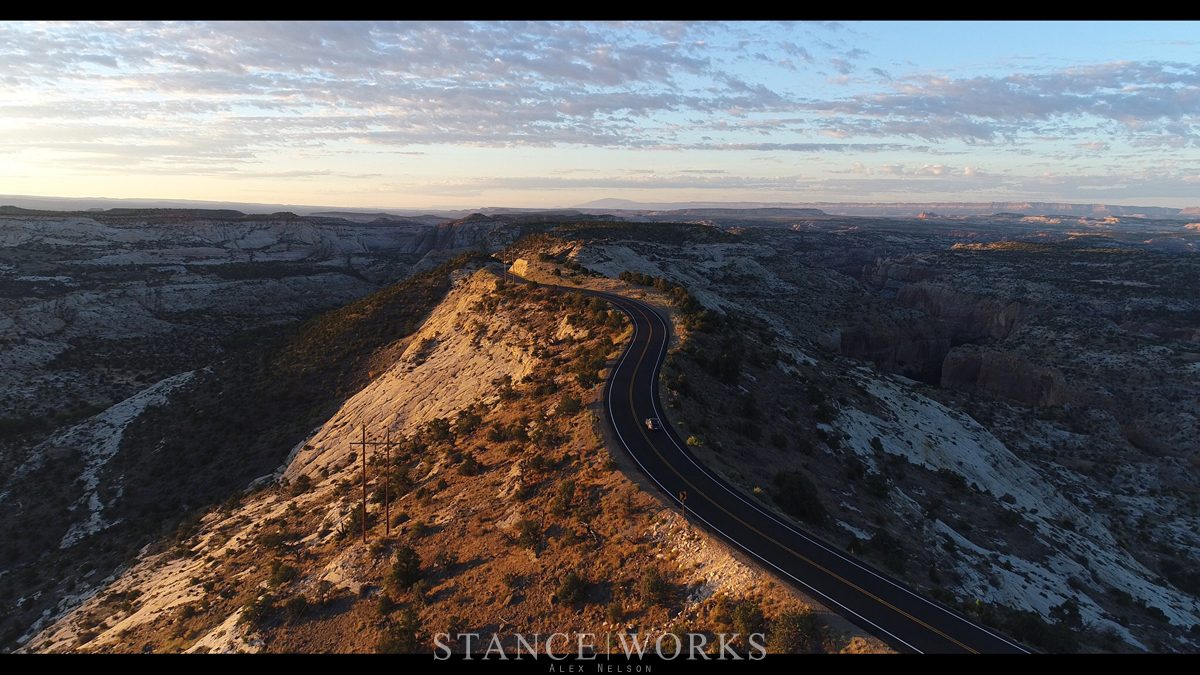

I woke up thinking one more sleep was ahead of me, and then it was off to the interstate for the haul home. We rose early to make the run to Hogback ridge, 20 miles east on route 12 from Escalante. Part of our route was aimed at getting there at sunrise. Driving through the switchbacks and hairpins at night isn’t as lonely as in the morning. At night, cars pass every so often. The camaraderie of the day lingers in the air, and you don’t feel alone. The very early morning brings a sense of isolation. My headlights lit the cliff walls, switching from left to right as we wrapped through the Grand Staircase National Monument. The road and the armco was new. The newly stamped barrier lit up, reflecting on the cliff opposite the road. It always seemed like there was an excuse not to drop the throttle on any roads. Road surface is too cold, there’s no shoulder, I’m down on power, it’s raining, I could die if I went off... That morning I put my conscience behind me and drove with purpose. The RSR muffler must have reached out for miles with no one to hear it. The car was overladen with fuel, equipment, and us. It felt heavy in the corners, but still predictable. Lift rotation felt slower, and more dangerous. I had set my odometer to help us know when we had reached Hogback ridge. I still wasn’t sure when we’d get there, as the odometer read 4% off. Dawn was coming, and a shallow pink peeked over the edge of the landscape.

The sunrise was underwhelming; with no moisture in the air it just snuck up on us. Stark shadows were cast, and there was a bit less contrast, but the coloring wasn’t much different than it would be later in the day. A quick and gentle sweep up a 14% grade between some rocks and we were there. I saw the road disappear off the horizon. Each side held no shoulder as it snaked back and forth across the spine of the ridge. There were no barricades in sight. I dropped Alex off so he could film and drove the road back and forth a few times. Out the window I could see the sun casting my shadow on the cliffs. I waved at myself. It’s like I’d met everything I wanted the drive home to be. I felt at that moment that I could be teleported away to never see or drive my car again because I’d never again experience anything like it. It was the only time I remember being alone on the trip, and it couldn’t have come at a better time. I reluctantly turned around and picked up Alex. I wanted to drive the ridge a few more times, but we had to keep moving.

After Utah, I’d had enough. I felt like I’d eaten my favorite Bolognese sauce my wife makes every day for the last 2 weeks, too much of a good thing. Enormous reservoirs and sprawling vistas left me unmoved. We flew through Disappointment Valley, still saying “wow” repeatedly but without the same sense of discovery. Colorado brought the biggest mountains we’d seen yet. We crossed the continental divide on our last day in the wilderness, our highest recorded point on the trip at 11,312 feet.

The way down would lead us to lunch with fellow Porsche enthusiasts in Nederland, CO. They were wonderful hosts, and offered to show us some of the best roads on our way north and east. I politely declined. I wanted to get as much of Nebraska out of my way as I could. I knew I was missing out. I saw roads branching off from the one I was on as we left Nederland. They looked amazing. I saw the twisty danger sign with 15mph listed below it more than once. I turned my head and looked away like I’d just seen someone I thought I might know, but didn't feel like talking to. It was sad. We fled across the interstate out of Colorado into Nebraska. It was stifling hot, 90 degrees and humid. We chased rain clouds hoping for some relief but never caught up. The elevation dropped, and as the heat of the afternoon fell away I was able to start making good time. My short gearbox regulates me to about 80mph. I only took one photo with my SLR between Colorado and Minnesota. There just wasn’t much to see from the interstate other than a rundown Super 8 and a few truck stops.

For me the drive ended with that wave in Utah. Looking back over the last several thousand miles I had to ask myself whether the trip was worth the risk, why I’d done it. Maybe underneath there’s another man in my subconscious who wants to wrestle with something dangerous, or defeat that needs to be conquered. A vintage 911 with all its quirks and dangers is just that: something to be conquered. Or, maybe it’s the 5-year-old boy in me, testing the limits of authority, inching his toes toward the edge of the cliff, watching over his shoulder for his grandfather to yell another warning. A 911 is rebellious in that way, pushing you, daring you, to step over the line of common sense, consequences be damned. Including our miles in California, it was well over 3500 miles of daring. The nostalgia, even a few months later, is perfect. I can’t wait to do it again.